Obituary: What Florian Schneider means for Düsseldorf

by Sven-André Dreyer

"Music visionary" from Düsseldorf

Our guide of the tour "The Sound of Düsseldorf" remembers Florian Schneider from Kraftwerk

The first time I met Florian Schneider was on a cassette. My uncle had recorded it for me and had taken great pains to do so, as he had photocopied the original cover, which was not yet in color at the time, and had painstakingly reduced it in size. It was the record "Kraftwerk" from 1970 and especially the piece "Vom Himmel hoch" liked me as a child particularly well. One hears, recorded by the legendary producer Conny Plank, at first mighty reverberated noises and a hardly classifiable sound carpet of acoustic and only partly electric instruments, which develops in the course of the altogether 10 minutes and 12 seconds long piece to a true inferno.

Acoustically, so I assumed as a child, air raids are simulated there, which eventually develop into a driving rhythm, which later in the piece makes powerful steam and is passably danceable. The nephew presented with the cassette was seven years old, and thus actually much too young to understand what he was holding in his hands. It wasn't just the humor underlying this early piece of the band's work. It was the legendary record itself, which bears the orange-and-white striped traffic pylon, the group's signature Kraftwerk symbol par excellence, on its cover. If you flip open the double cover, you'll see a black-and-white photograph of a transformer pumping its electrical voltage into the copper wires. The photograph is by Bernd and Hilla Becher, and already in 1970 it illustrates how intense the exchange of visual art was in the environment of the Düsseldorf Art Academy and the new music scene from Düsseldorf.

And if you look today, 50 years later, at the small photo of Florian Schneider-Esleben, also printed inside the cover, you are once again amazed: Schneider is playing the flute in the photo, and yet only a few years later he was to put the instrument he had studied at the Robert Schumann Conservatory in his hometown aside forever to set off into new worlds of sound, becoming one of the world's most influential electronic musicians in the process.

Florian Schneider grew up as the son of the architect Paul Schneider-Esleben. He not only built Cologne-Bonn Airport, but also created groundbreaking architecture in his hometown. One example is the Mannesmann Tower on Düsseldorf's Mannesmann-Ufer. Almost 90 meters high and now a listed building, the client himself once supplied some of the material for the construction of the high-rise, which was completed in 1958. And with the design of the glass Haniel Garage on Schlüterstrasse, completed in 1953 and Germany's first parking garage and motel after the war, the renowned architect had already further developed the German tradition of classical modernism and achieved international fame. A family environment that was to have a lasting influence on Schneider, as his family was always in contact with the leading, internationally renowned artists of the time.

Together with his student friend Ralf Hütter, Schneider finally set out to overturn and completely rethink the music that had been created up to that point. The subsequent records became increasingly electronic, Autobahn, Radio Activity, Trans Europa Express, and the aesthetics increasingly cool. Avant-garde from Düsseldorf. And also the musicians took - as far as their appearance was concerned - a clear change. While they still wore their hair long in the early photos, they already looked more like civil servants in the mid-1970s, and at this point at the latest they finally broke with musical tradition and the acoustic dictates from Great Britain and overseas.

Not only were their lyrics sung in German, the entire appearance of the band, which from then on became more and more silent, seemed to have fallen out of time, the musicians like extremely progressive German engineers nonetheless. The courage to experiment with sound, the ever-growing fleet of electronic, mostly self-built instruments, the visionary approach of staging music not only acoustically but as a complex concept, and not least the concentrated creativity of the musicians Schneider and Hütter ultimately made the band a total work of art to this day.

Their musical minimalism became a pattern and was extremely influential in the long term, influencing entire generations of musicians with their style. For example, their rhythms were first sampled in the New York hip-hop scene, and Kraftwerk was also a major inspiration for the early techno that emerged in Detroit from the mid-1980s onward. Kraftwerk's declared goal, at the latest with the release of the 1978 album "Die Menschmaschine," was to not only strictly and formally decline their music; above all, the desubjectification of their work became increasingly important to the musicians.

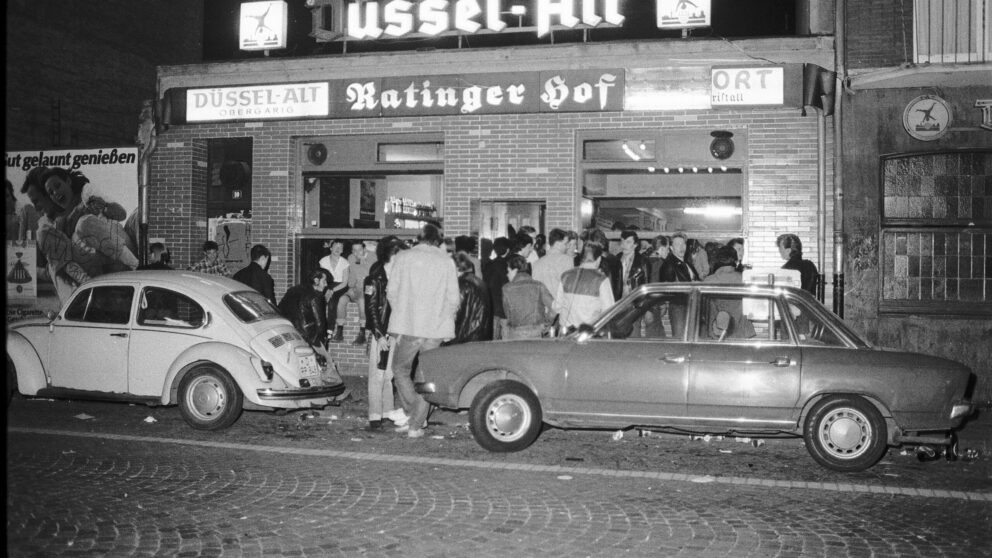

This also included underpinning and weaving around Hütter's actually quite passable singing voice with increasingly complex, vocoded vocal passages. It was Schneider in particular who worked feverishly - by electronic means and later computer-aided - to dehumanize the human voice and to fathom anew the boundaries between man and machine. And yet: Florian Schneider always remained true to his hometown of Düsseldorf as a person in the flesh. Not only because of the KlingKlang studio set up as early as the late 1960s on Mintropstraße, and thus in the middle of the red light district, where the musicians worked behind closed doors and near the main train station until the late 1990s.

Here in Düsseldorf, Schneider also received his international guests - such as David Bowie and Iggy Pop, who, according to his own statement, were significantly inspired by the sound from the Rhine. It was from here that Florian Schneider's band sent out its influential and groundbreaking signals to the musical world until very recently.

If we play their piece "The Model" today on our musical city tour "TheSound of Düsseldorf" at Düsseldorf's Königsallee, the international guests will also stop and listen to the timeless electronic pop made in Düsseldorf.

The special thing: As shy as Florian Schneider sometimes appeared, he was nevertheless present in Düsseldorf's cityscape. You could meet him at lunchtime on Carlsplatz for a pea soup or for an espresso at Caffè Enuma on Suitbertusstraße in Bilk. And sometimes Florian Schneider even gave away a smile during one of these brief encounters. Afterwards, they nodded silently to each other and went their separate ways again. Always in the certainty that they would meet again soon. A few days after his 73rd birthday on April 7, 2020, Florian Schneider died as a result of a brief bout with cancer.

Photos: Markus Luigs